A banditry of titmice.

January was the first time I have ever seen a flock in our yard. We often have robins, cardinals, and juncos, but a dozen titmice with their tan little crests were a new sight.

Scavenging the stone pavers where I scatter birdseed in the winter, they quickly flew about the ground and under bushes as they hunted collectively for food. They knew to prepare as temperatures dropped further that night.

In those same weeks, my husband and I were fasting with our church body. Creature comforts like bread, desserts, TV were denied. I may have been grumpy. Though I disliked not having the freedom to watch a movie on the weekend, I did find more room, more stillness, for reading, prayer, and sleep. They may be the stores, the reserves, of my winter preparation for the next season.

Favorites from the archives

Leo Tolstoy’s Confession was first published at my website on April 29, 2021.

I like landing upon a book that causes me to pause, to slow my reading. My desire to absorb what I read surpasses my desire to finish the book, even such a short one as A Confession.

Leo Tolstoy was 51. Having gained fame and fortune after publishing War and Peace (1869) and Anna Karenina (1877), he earnestly questioned his purpose in life. Tracing his childhood and young adult life at first, Tolstoy admits that he never thought about what he believed or why. He saw no reason to continue in the Orthodox Christianity he was brought up in. People at a certain level of education didn’t need faith, he thought. “Then as now, it was and is quite impossible to judge by a man's life and conduct whether he is a believer or not.”

Tolstoy did not see how religious doctrine played a part in anyone’s life—“in intercourse with others it is never encountered, and in a man's own life he never has to reckon with it.”

Instead of pursuing what he saw as an empty faith, he says, “I tried to perfect myself mentally—I studied everything I could, anything life threw in my way; I tried to perfect my will, I drew up rules I tried to follow.” His self-centered attempts soon led to wanting to appear more perfect than others.

So he did whatever he wanted, and the older he grew, and the more he watched others, he knew he had to make progress. He wanted to be good but saw that he was alone in this desire. As he describes his military life, Tolstoy lists all of his sins, but as he turned to writing in his twenties, his fellow writers were no different at heart than the soldiers and officers he lived among for so long. It wasn’t long before he realized that “the superstitious belief in progress is insufficient as a guide to life. I had to know why I was doing it.”

It makes me remember a phrase from long ago, “the cult of progress.” In a writer’s life today, it’s still a mantra.

But then in Chapter 3, Tolstoy turns his thoughts to education as he considered plans for his own children someday. “I would say to myself: ‘What for?’” He was really asking how do we teach if we’ve never been taught—

In reality I was ever revolving round one and the same insoluble problem, which was: How to teach without knowing what to teach. In the higher spheres of literary activity I had realized that one could not teach without knowing what, for I saw that people all taught differently, and by quarreling among themselves only succeeded in hiding their ignorance from one another. But here, with peasant children, I thought to evade this difficulty by letting them learn what they liked. It amuses me now when I remember how I shuffled in trying to satisfy my desire to teach, while in the depth of my soul I knew very well that I could not teach anything needful for I did not know what was needful. After spending a year at school work I went abroad a second time to discover how to teach others while myself knowing nothing.

Tolstoy clearly recognizes the voids within him. He tried to replace an absence of faith in God with a faith in himself. He tried to give himself purpose, trying to attain status and fame in the military and as a writer before turning to teaching peasant families, all before he married and had a family. His striving left him empty, and with his retrospective, Tolstoy saw himself for what he lacked.

I’ve only read these first chapters of A Confession, and I think I’ll reread them before moving on. Maybe it’s because I’m near the same age as he was when he examined his life. Maybe it’s because, when I'm alone, I question the fruitfulness of my life. Regardless, Tolstoy gives us much to ponder. What do we truly value? Do I know what I believe? Do I know my purpose?

On my nightstand

C.S. Lewis’s The Last Battle (1956). Always deep, always a tough read emotionally and spiritually, always worthwhile every time I read of the last days of Narnia.

Lore Ferguson Wilbert’s The Understory: An Invitation to Rootedness and Resilience from the Forest Floor (2024). An unusual blend of spiritual memoir and the science of the woods, it was hard for me to follow as a reader since each chapter was divided (or interrupted) into multiple anecdotes of different styles, but Wilbert also tackles some heavy subjects. I felt incredibly sad when I finished, but many reviewers loved its rawness.

Eugene H. Peterson’s Tell It Slant: A Conversation on the Language of Jesus in His Stories and Prayers (2008). I am starting this Christmas gift this week!

What about you? What are your winter stores? What are you reading? I would love to hear from you in your reading or classroom journey.

As always, thanks for reading and listening! Don't forget that the List Library at my website is always available to you, my readers.

Christine

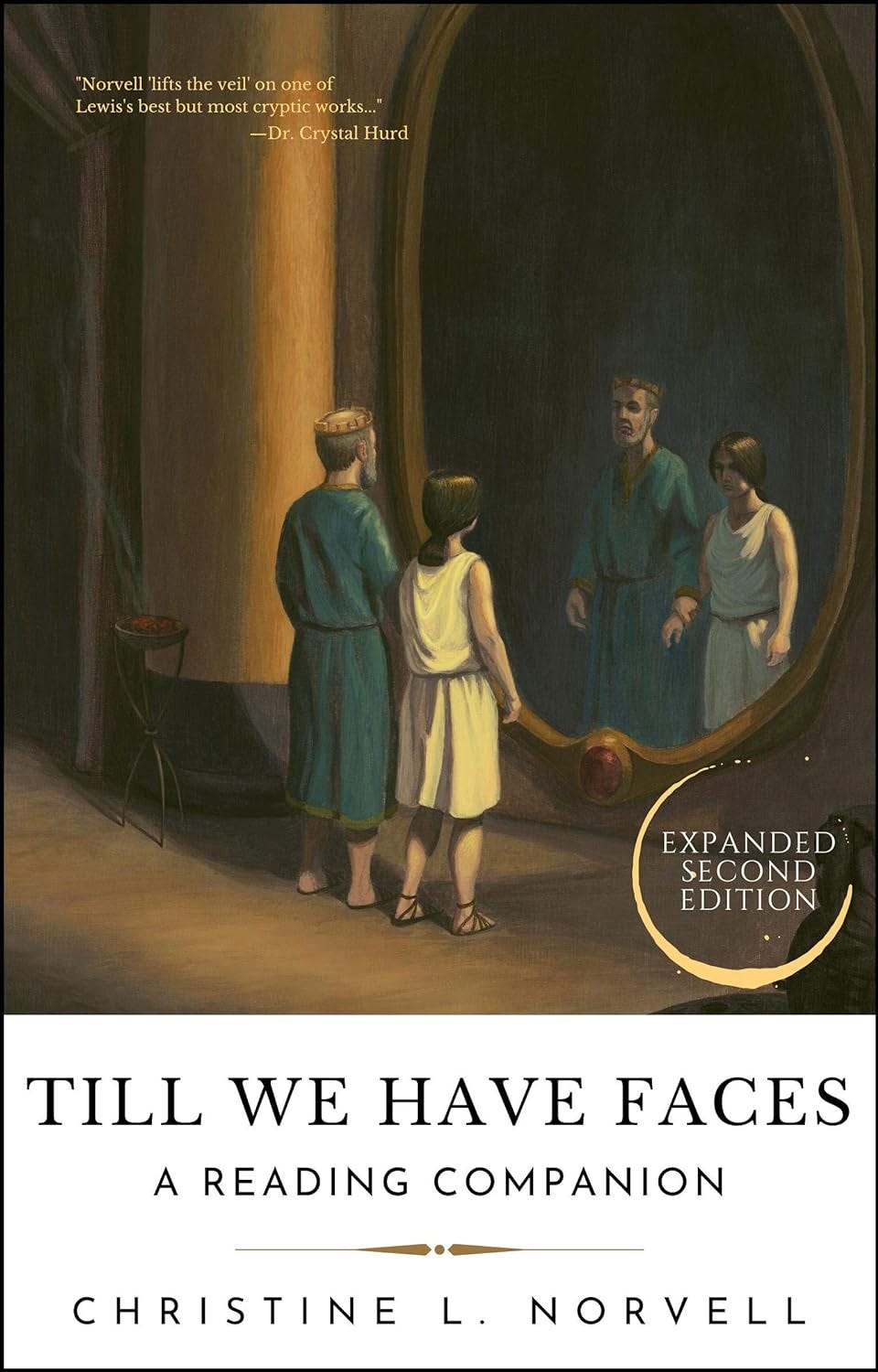

Perfect for beginners, this handy study guide for C.S. Lewis's novel is a blend of summary and scholarly commentary. The second edition includes leading commentary from Lewis scholars as well as key parallels from Lewis’s other works like The Four Loves, Surprised by Joy, and An Experiment in Criticism. Each chapter includes discussion questions designed for students, teachers, book clubs, and church groups. Available at multiple online stores or at Amazon.

I enjoyed reading this, Christine. I also question my fruitfulness when I'm alone, and it's encouraging to remember the lives of others and the thoughts they wrestled with.

Wonderful insights, and I particularly appreciate your comments on Tolstoy. He was an interesting man.