Welcome to my newest readers, fellow bibliophiles, and educators!

Over a century ago, my mother and my father’s families immigrated to Nebraska, settling as farmers and building God-fearing communities. When I was young, we drove long hours from Mississippi to visit grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins in the summer and at Christmas. It seemed as if everyone I met was a cousin of a cousin.

Some of my most distinct memories center around irrigation ditches. Yes, ditches. I can hear the low voice of my grandfather chatting with me and my sister as he looked along the corn rows and let us play. Black earth, cold well water, and catching frogs in the heat of the summer sun.

Like a golden haze, there’s a sentimentality to my Nebraska memories, and I recognize that in the literary work of Willa Cather. Her pioneer trilogy remains dear to me, so it was a delight to share a paper on those novels and more last weekend.

John and I drove to Dallas for the Southwest Conference on Christianity and Literature. It was our first time to attend, and we enjoyed long and meaty conversations with lots of people, including

and .I might not share a full paper here, but I can leave you a small taste of “Willa Cather and the Good Land.”

In the world of story, there is no doubt that setting plays a vital role. It lends atmosphere and stirs mood. It sparks our imagination and relays emotion. As readers, we want to see and feel and breathe the world the characters live in. Many times, the setting itself becomes a character. One such example is the land within many of Willa Cather’s novels and short stories. It possesses a full personality, eccentric and independent. Though the land in Cather’s works is often antagonistic, her descriptions show us a responsive land uniquely parallel to the biblical laws of stewardship in the Old Testament. As with the law of sowing and reaping, the land responds in kind to how it is tended, whether for good or ill, in bounty or famine. At its heart, it is not an antagonist as some scholars believe, but the good land God has given (Deuteronomy 8:10).

Around the web

For my fellow educators, I highly recommend subscribing to Cana Academy’s weekly newsletter aptly called “The Toolkit.” Veteran classical educator Andrew Zwerneman provides blog articles, reading suggestions, webinars, and lots of free goodies through their website. And if, like me, you are training new or newer teachers in discussion methods, I found that Jeannette Zwerneman’s A Lively Kind of Learning: Mastering the Seminar Method is extremely helpful. She offers six patterns of discussion as well as help for troubleshooting common mistakes.

Favorites from the archives

This article first appeared in StoryWarren on March 9, 2022.

I’m no stranger to George MacDonald. In fact, I would say I often feel like his welcome companion when I’m immersed in his fiction. A Quiet Neighborhood, Castle Warlock, or Sir Gibbie are places I’ve been to, and people I’ve visited in my imagination. But MacDonald also wrote a number of essays commenting on the fairy tale genre and his own writing.

In “The Fantastic Imagination,” MacDonald clarifies that fairy tales really have nothing to do with fairies, or at least they don’t have to. They do, however, have a “natural law” unto themselves as MacDonald writes. Our imagination won’t work without it.

This is what he means. When we create from our imaginations and write a story, we naturally follow a pattern of harmony. MacDonald explains it this way: If you were to give a bizarre accent to “the gracious creatures of some childlike region of Fairyland,” then wouldn’t the tale sink then and there? The pieces of the tale must harmonize and not stick out.

Inharmonious, unconsorting ideas will come to a man, but if he try to use one of such, his work will grow dull, and he will drop it from mere lack of interest. Law is the soil in which alone beauty will grow; beauty is the only stuff in which Truth can be clothed; and you may, if you will, call Imagination the tailor that cuts her garments to fit her, and Fancy his journeyman that puts the pieces of them together, or perhaps at most embroiders their button-holes. Obeying law, the maker works like his creator; not obeying law, he is such a fool as heaps a pile of stones and calls it a church.

MacDonald continues with a lively question and answer section in his essay. He repeats questions I’m sure he must have heard many times during his literary tours at home and abroad.

“You write as if a fairytale were a thing of importance: must it have meaning?”

“If so, how am I to assure myself that I am not reading my own meaning into it, but yours out of it?”

“Suppose my child asks me what the fairytale means, what am I to say?”

And so on. We each bring our own meaning to what we read and what we experience as we read, but children don’t worry about such things. It seems only adults do.

This is where MacDonald introduces us to my favorite simile. Maybe it’s because it’s a musical term. Maybe it’s because it’s not black and white. But MacDonald says, “The true fairy tale is, to my mind, very like the sonata.” He argues that words aren’t as precise as we suppose. If a few men were to listen to a sonata and then write down what they thought it meant, the very action would destroy its effect upon them.

The tale is to be experienced, not analyzed. It is for the beauty, not for facts and knowledge. It should stir and wake us. “The best way with music, I imagine, is not to bring the forces of our intellect to bear upon it, but to be still and let it work on that part of us for whose sake it exists.”

Read MacDonald’s full essay at the George MacDonald Society.

On my nightstand

Patrick Lencioni’s The Advantage: Why Organizational Health Trumps Everything Else in Business (2012).

Raymond Heiser’s Following Jesus as a Disciple (2024). (That’s my Dad!)

William Stearns Davis’s Life on a Medieval Barony (1923).

Let me know your book stories. What are you reading? What are you finding helpful? I would love to hear from you in your reading or classroom journey.

As always, thanks for reading and listening! And yes, my audio link at the beginning of the newsletter will return soon. Don't forget that the List Library at my website is always available to you, my readers.

Christine

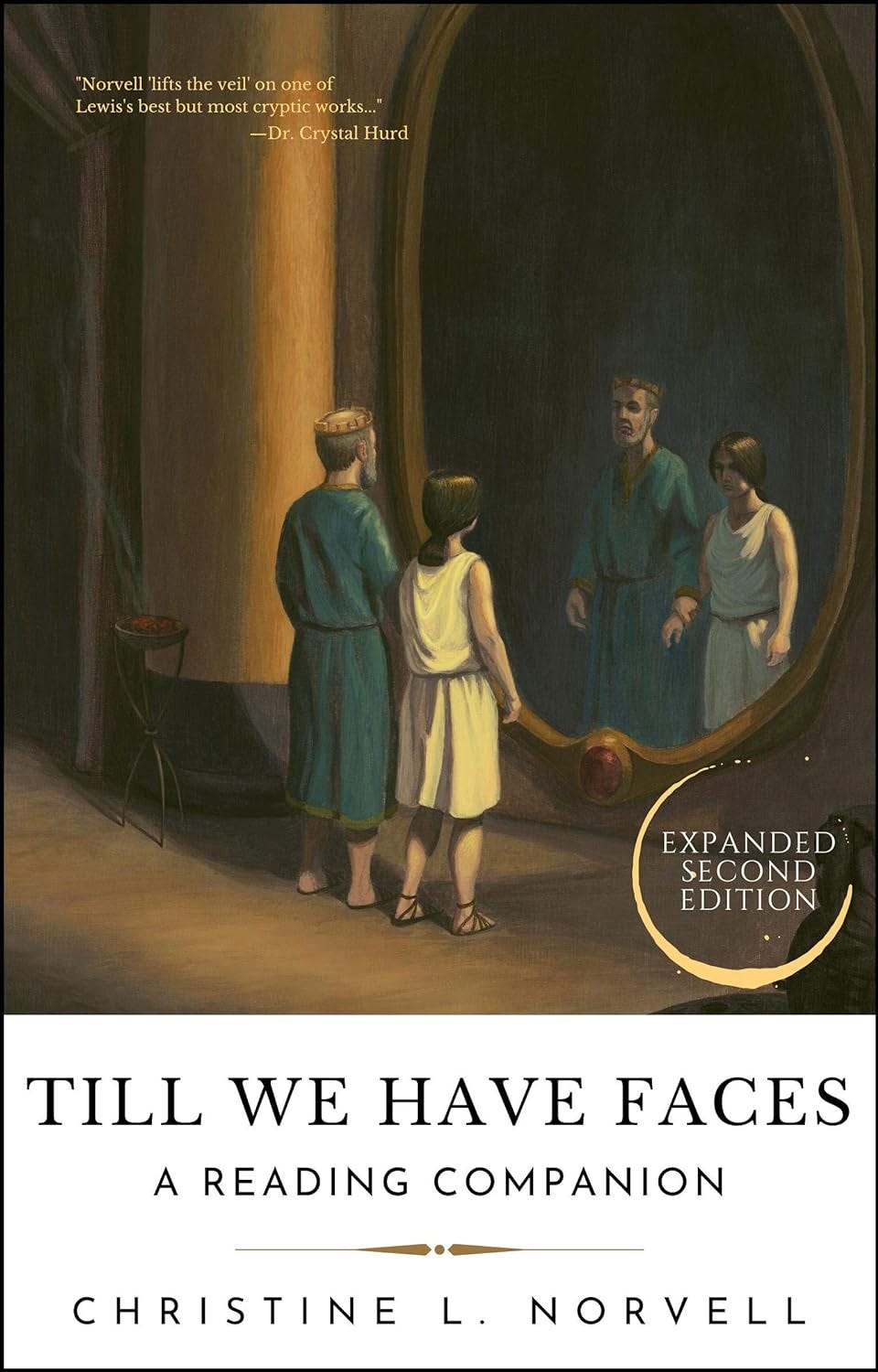

Perfect for beginners, this handy study guide for C.S. Lewis's novel is a blend of summary and scholarly commentary. The second edition includes references to leading commentary from Lewis scholars as well as key parallels from Lewis’s other works like The Four Loves, Surprised by Joy, and An Experiment in Criticism. Each chapter includes discussion questions designed for students, teachers, book clubs, and church groups. Available at multiple online stores or at Amazon.

I hope there are more conversations in our future